A Meat Eater’s Delight

By Kurma Dasa

In 1996 Kurma published a seven-hundred page book on the history of the Hare Krishna Movement in Australia entitled “The Great Transcendental Adventure”. The book also serves as a biography of the movement’s founder and Acharya, His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, affectionately known as Srila Prabhupada.

The following essay is an excerpt from that book.

Dawson Avenue, Brighton

Tuesday 25 June, 1974.

Dipak had volunteered for the service of cooking lunch for Prabhupada during his visit to Melbourne. Yet Dipak, usually a proficient cook, was today not his usual confident self. He was nervously dropping butter on the floor, sliding chapatis off the stove and boiling over the milk when he noticed Srila Prabhupada at the kitchen door.

Prabhupada, standing bare-chested after his bath, was smiling as he watched Dipak’s attempts to cook lunch. Returning to his room, Srila Prabhupada applied the sacred marks of Vaisnava tilaka with great attention and sat, head slightly back, to chant his noon-time Gayatri mantra prayers.

Meanwhile, Dipak was coming to the end of a very chaotic morning in the kitchen. He quickly poured freshly-squeezed lemon juice into the pot of steaming hot basmati rice, spooned out a generous serving, adjusted the bowls of dal and vegetables, popped on a couple of hot chapatis and raced the plate into Prabhupada’s room.

Prabhupada sat on a low cushion behind his glass-topped table, on the white-linen-covered floor. He nodded appreciatively as Dipak placed the plate on the table, offered respects and quickly exited.

Feeling relieved that lunch was on time, Dipak returned to the kitchen to clean up the scene of devastation. He especially hoped that Srila Prabhupada would enjoy the rice today. He had recently heard, although he couldn’t remember where from, that Prabhupada liked lemon juice on it.

Satsvarupa Goswami, Prabhupada’s secretary for this visit, broke Dipak’s daydream. “Dipak! Srila Prabhupada would like to see you.” Dipak wiped his hands and rushed into the room.

Prabhupada was looking up inquisitively. “What is the matter with this?” he asked, pointing to the untouched mound of rice on his plate. “It is sour!” Dipak stumbled out an answer. “Oh… er… I put lemon juice on it, Srila Prabhupada.” Prabhupada looked disappointed. Dipak volunteered to cook more.

“No,” Srila Prabhupada answered. “Bring some milk and sugar.”

Srila Prabhupada sprinkled sugar all over the rice, poured on the milk, and took it as dessert. After lunch, Prabhupada again called Dipak into his room. “Tomorrow,” he reassured, “I will teach you how to cook.”

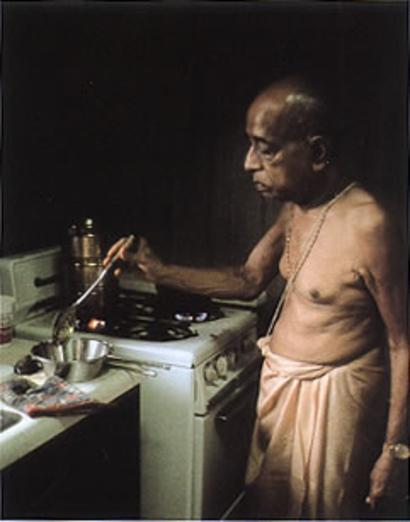

Next day Srila Prabhupada entered the kitchen around mid-morning. Despite Melbourne’s cold winter, the sun shone brightly through the windows of the little kitchen. Prabhupada stood without his shirt, his soft, golden skin glowing. He looking serious; his mood was that of an instructor. Forewarned, the devotees were peering in through the back screen door and peeping through the windows to witness the exciting event.

Prabhupada expertly directed the whole scene. Step-by-step, he taught the timeless cooking art by demonstration: “Cut like this… add this much… fry like this…” All the while, Prabhupada cooked with silent concentration, cleaning the stove and sink after each step, and periodically checking his wrist watch.

The crisp, white cauliflowerets and cream-colored potato chunks were cut to size. Next they were placed in one compartment of Prabhupada’s shiny three-tiered brass cooker, the same one that he had brought to America in 1965, which sat on the small square stove. The rice and water were placed in another compartment; mung beans, water and turmeric in the third.

“Turmeric,” Prabhupada pointed out, “is a blood purifier.”

Today he would show Dipak a special rich vegetable dish. He directed Dipak to cut eggplants into very large cubes, almost five centimetres square. Panir cheese, which Dipak had made earlier,was cut into similarly sized chunks. The potatoes were cut only slightly smaller. All were deep-fried in small batches in the pan of fresh, hot clarified butter, ghee. Prabhupada stressed that the panir cheese had to be cooked until very dark brown. There was no joking and no talking other than these serious instructions.

Dipak’s chapati dough had been too dry and hard, so Srila Prabhupada made another batch which he had subsequently submerged in a bowl of water. Draining off the water and kneading in a little more atta flour, Prabhupada indicated the correct consistency: “As soft as your ear-lobe,” he said, squeezing his own left ear to demonstrate.

When the vegetables and panir cubes were all fried, Srila Prabhupada heated some ghee in a saucepan and deftly sprinkled-in cumin seeds and crushed red chillies. As the spices darkened, he added a sprinkle of asafoetida and turmeric, and a little crushed fresh tomato. The pan hissed and sizzled, especially when Prabhupada poured in a few cups of fresh whey, the liquid residue from the panir cheese. He slid the potatoes and panir cubes into the pan, followed by the eggplant and salt, and simmered them slowly.

Next he heated another small pan, added some ghee and spices and the cooked potatoes and cauliflower from the steamer, and briefly sautéed them, pouring in a little water to form a gravy which thickened and stuck to form a sizzling crust. Ghee was heated in a third little pan, and cumin, chilli and whole coriander seeds were heated, browned, and thrown crackling into the smooth, yellow dal soup. Srila Prabhupada finally spooned off the whole spice seeds from the simmering dal, then left for his massage and bath.

After bathing, he re-entered the kitchen and cooked the first few chapatis which all obediently ballooned, emitting little puffs of steam as they reached their bursting point.

Everything was done in exactly one and a half hours, including the massage and bathing. Srila Prabhupada finally sat down, the cooking class completed, and prepared to take his lunch.

Pointing to the large, rich, dark chunks of fried panir cheese, now puffed and juicy from slow simmering in seasoned gravy, he smiled and looked up at Dipak. “You should cook this for the meat-eaters. They will very much appreciate. It is a ‘meat-eater’s delight’.”

For the cooks at the Melbourne branch of Srila Prabhupada’s International Society for Krsna Consciousness, this was an historic culinary moment.

Source: www.kurma.net